There was a time when the sound of ABBA seemed to flow through the veins of Sweden itself — bright, clean, and alive, like sunlight breaking through Scandinavian clouds. From living rooms in Stockholm to frozen train platforms in Kiruna, their music wasn’t just popular; it was part of daily life. “Mamma Mia”, “Fernando,” “Dancing Queen,” “Knowing Me, Knowing You” — songs that somehow turned everyday emotions into something larger, almost spiritual.

There was a time when the sound of ABBA seemed to flow through the veins of Sweden itself — bright, clean, and alive, like sunlight breaking through Scandinavian clouds. From living rooms in Stockholm to frozen train platforms in Kiruna, their music wasn’t just popular; it was part of daily life. “Mamma Mia”, “Fernando,” “Dancing Queen,” “Knowing Me, Knowing You” — songs that somehow turned everyday emotions into something larger, almost spiritual.

The world sang with them. But back home, something more profound happened. For the first time, Sweden — small, reserved, often content to stand quietly at the edge of global culture — had a sound that belonged entirely to itself.

And then, almost overnight, it disappeared.

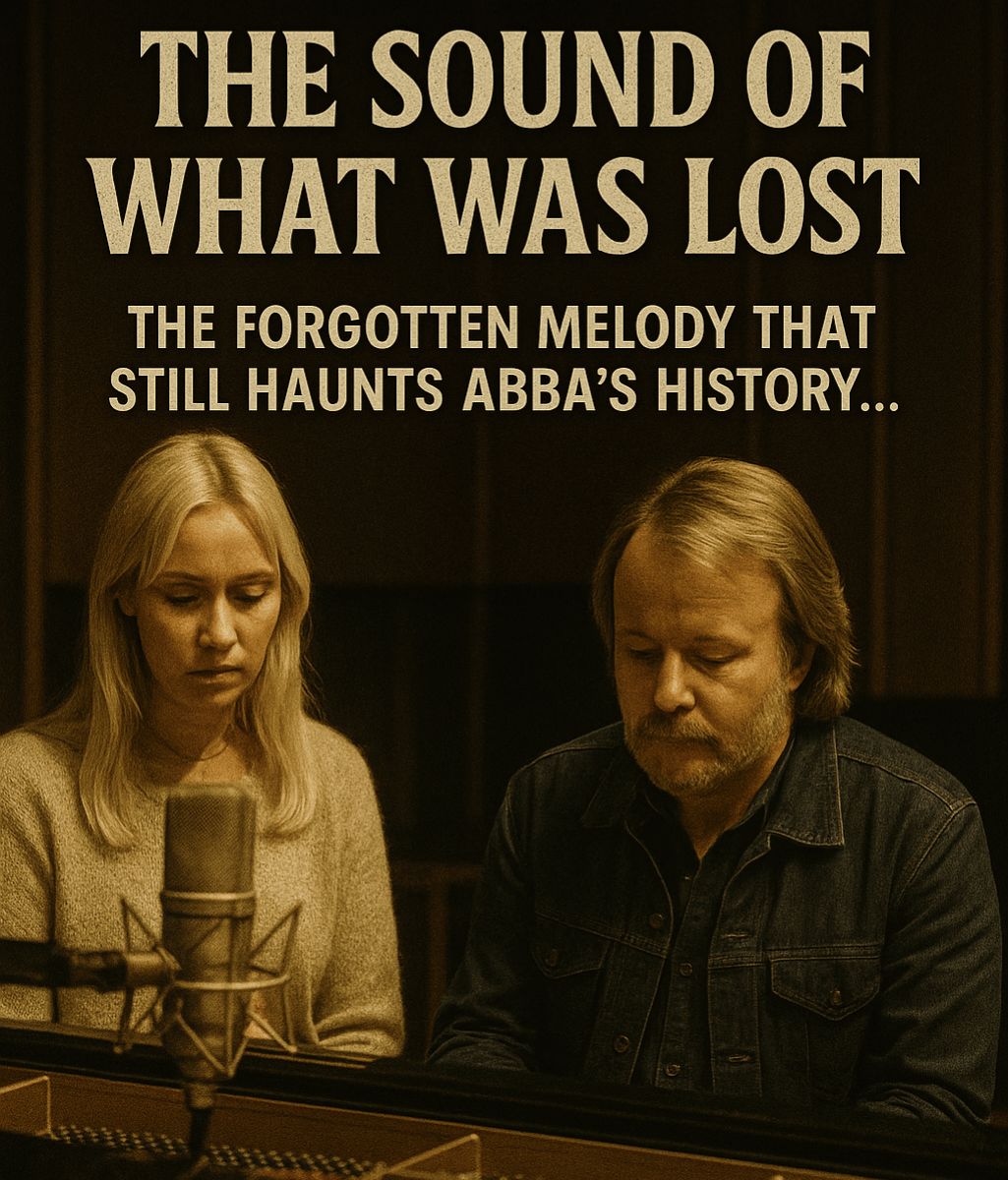

When ABBA went silent in 1982, there was no public farewell. No confetti, no final bow, not even a closing chord. The band simply slipped out of view — four people who had given everything to music, love, and each other, now choosing stillness. “We didn’t end,” Benny Andersson later said. “We just stopped.”

But the silence that followed wasn’t ordinary. In a country so defined by their sound, it felt as though a season had ended — one that would not return. The joy that had filled every street parade, wedding, and radio station in the 1970s seemed to fade into something quieter, lonelier.

Sweden entered what many later called the cultural winter.

For years, no other artist came close to filling the space ABBA left behind. There were new genres, of course — punk, metal, electronic — but none carried the same open-hearted optimism. Where ABBA had once sung about love and second chances, the next generation sang about disillusionment, isolation, and snow.

And perhaps that made sense. Because ABBA had not only written about joy; they had written about the cost of it — about the fragility of love in a world that keeps changing.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the Swedish government began funding new music schools, record labels, and technology incubators. The dream was to turn heartbreak into innovation — and, astonishingly, it worked.

Out of ABBA’s silence came a wave of creation that reshaped the music world once again. Max Martin, the quiet genius behind hits for Britney Spears, Backstreet Boys, Taylor Swift, and The Weeknd, grew up studying the same melodies and harmonies that Benny and Björn had perfected. “ABBA taught us structure,” Martin said. “They showed that even pop could be emotional poetry.”

By the turn of the millennium, Sweden — a country of barely 10 million people — had become the world’s third-largest exporter of music, behind only the United States and the United Kingdom. From Roxette and Ace of Base to Avicii and Zara Larsson, every artist carried, in some invisible way, the DNA of ABBA’s songwriting.

Yet, even as the music returned, the tone was different. The warmth of the 1970s had cooled into sleek precision — polished, powerful, but somehow distant. The songs were global, but not always personal. Sweden had found its rhythm again, but perhaps lost a little of its innocence.

Then, in 2021, the silence broke.

When ABBA announced “Voyage” — their first album in forty years — the reaction was not hysteria, but something deeper: relief. The nation that had learned to live without its song finally heard it again. And it wasn’t nostalgia. It was healing.

The new music was slower, wiser, touched by time. “I Still Have Faith in You” felt like a letter from the past to the present — a confession that love, though changed, still endures. Agnetha Fältskog’s voice, trembling and luminous, carried all the years between then and now. “It’s us,” Björn Ulvaeus said. “Older, yes — but still us.”

In Stockholm, fans gathered outside the ABBA Museum, holding candles, tears mixing with laughter. People who had grown up with their records brought their children and grandchildren, saying, “This — this is who we are.” For a few weeks, the country felt alive in a way it hadn’t in decades. The air buzzed again with the sound of shared memory.

💬 “It wasn’t just about music,” said one Swedish journalist. “It was about belonging. ABBA gave Sweden its reflection back.”

Today, Sweden is a global powerhouse of pop. But walk through Djurgården at dusk, past the museum where ABBA’s gold suits glitter behind glass, and you’ll feel something gentler — a melancholy pride, an understanding that the music was never really just about success.

It was about resilience. About a people learning to find beauty in restraint. About four artists who took their private heartbreaks and turned them into universal hymns.

Even now, the echoes remain — in film scores, in Eurovision anthems, in the way Swedish pop continues to blend joy with longing. Because ABBA never truly ended. They became part of the language.

“A country without its song,” one Swedish critic once wrote, “is a country without its memory.”

But Sweden never lost its memory. It simply waited — quietly, patiently — for the music to return.

And when it did, it wasn’t about fame or glitter or disco lights.

It was about coming home.

Because for Sweden, ABBA wasn’t just a band.

They were — and still are — the sound of its soul.